Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com

Please check out my new blog at mas-bandwidth.com!

Introduction

Hi, I’m Glenn Fiedler. Welcome to Virtual Go, my project to create a physically accurate computer simulation of a Go board and stones.

In the previous article we detected collision between the go stone and the go board. Now we’re working up to calculating collision response so the stone bounces and wobbles before coming to rest on the board.

But in order to reach this goal we first need to lay some groundwork. It turns out that irregularly shaped objects, like go stones, are easier to rotate about some axes than others and this has a large effect on how they react to collisions.

This is the reason go stones wobble in such an interesting way when placed on the go board, and why thick go stones wobble differently to thin ones.

Let’s study this effect so we can reproduce it in Virtual Go.

Rotation in 3D

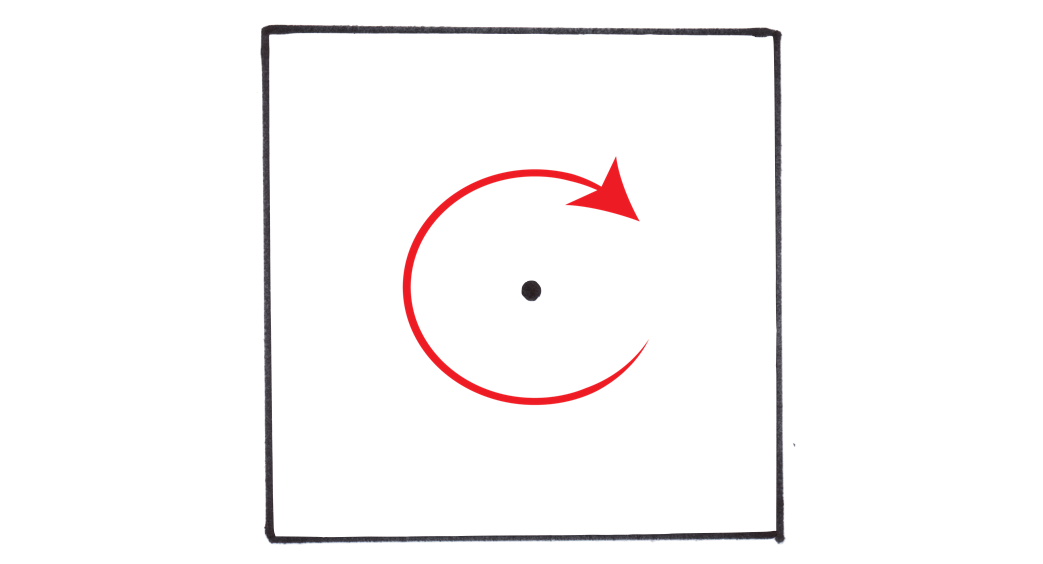

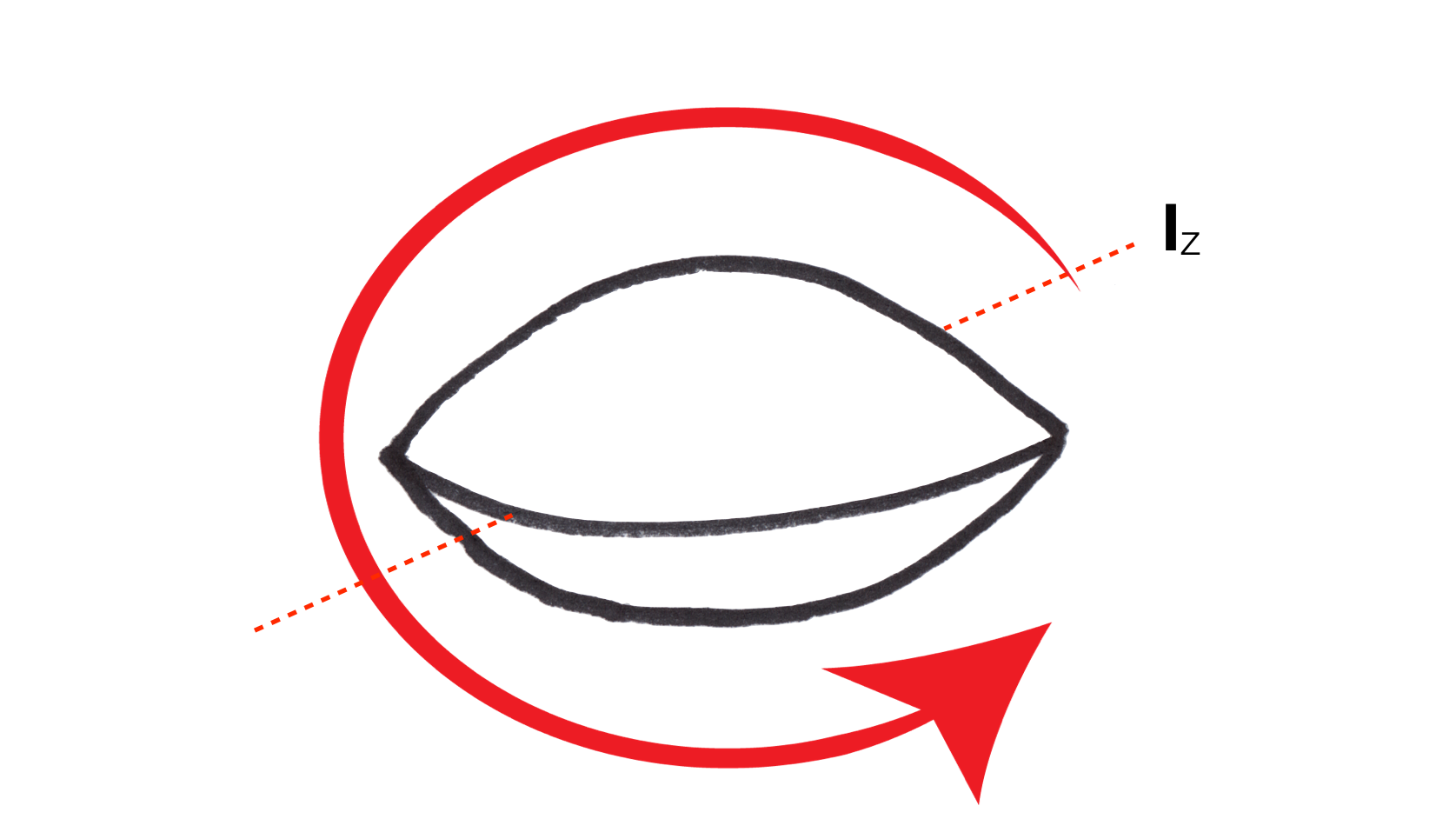

Consider the following case in two dimensions:

It’s easy because there is only one possible axis for rotation around the center of mass: clockwise or counter-clockwise.

It follows that we can represent the orientation of an object in 2D around its center of mass with a single theta value, angular velocity with a scalar radians per-second, and a scalar ‘moment of inertia’ that works just like an angular equivalent of mass: how hard it is to rotate that object.

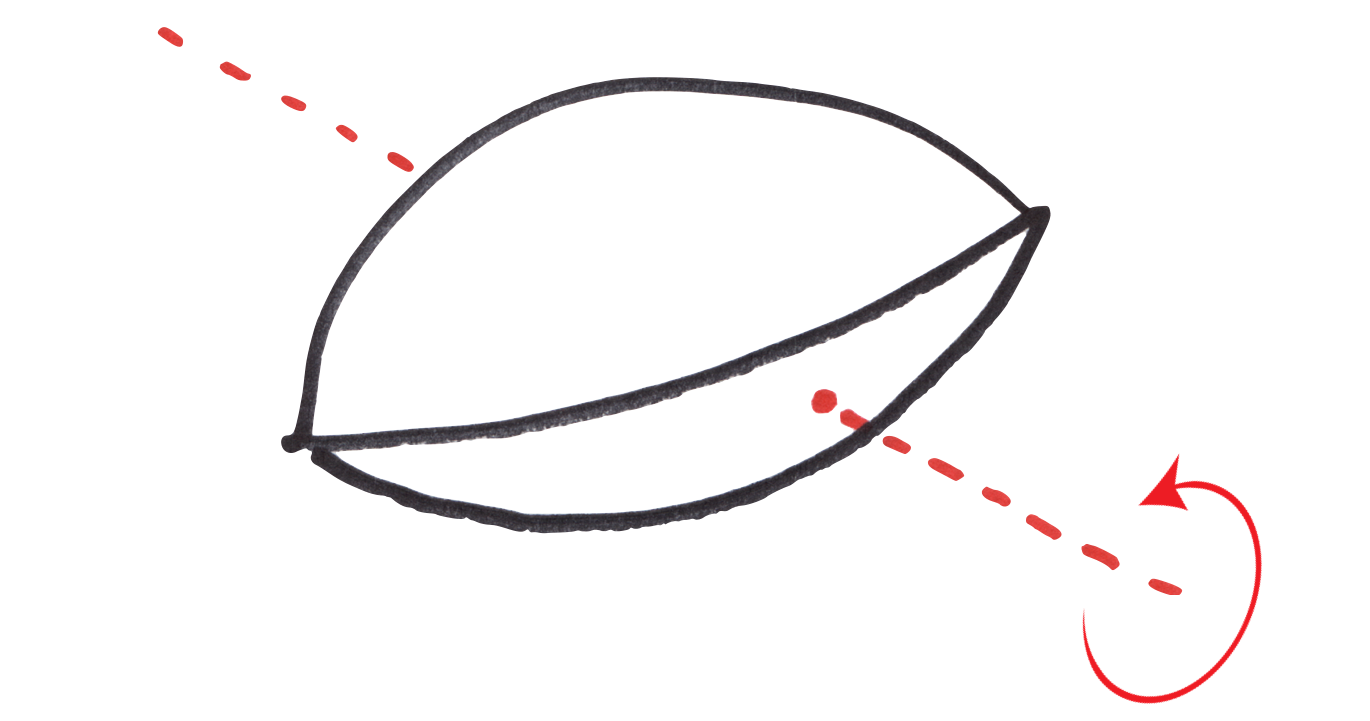

But when we move to three dimensions suddenly rotation can occur about any axis. Orientation becomes a quaternion, angular velocity a vector, and now for irregular shaped objects like go stones, we need a way to indicate that certain axes of rotation are easier to rotate about than others.

But how can we represent an angular mass that depends on the shape of the object and the axis of rotation?

Inertia Tensor

The solution is to use an inertia tensor.

An inertia tensor is a 3x3 matrix with different rules to a normal matrix. It rotates and translates differently, but otherwise behaves like a 3x3 matrix and is used to transform angular velocity to angular momentum, and the inverse of the inertia tensor transforms angular momentum to angular velocity.

Now this becomes quite interesting because Newton’s laws guarantee that in a perfectly elastic collision angular momentum is conserved but angular velocity is not necessarily.

Why is this? Because angular velocity now depends on the axis of rotation, so even if the angular momentum has exactly the same magnitude post-collision the angular velocity can be different if the axis of rotation changes and the inertia tensor is non-uniform.

Because of this we’ll switch to angular momentum as the primary quantity in our physics simulation and we’ll derive angular velocity from it. For consistency we’ll also switch from linear velocity to linear momentum.

Calculating The Inertia Tensor

Now we need a way to calculate the inertia tensor of our go stone.

The general case is quite complicated because inertia tensors are capable of representing shapes that are non-symmetrical about the axis of rotation.

todo: yes, need to sort out the latex equations…

[latex]I = \begin{bmatrix} I_{xx} & I_{xy} & I_{xz} \ I_{yx} & I_{yy} & I_{yz} \ I_{zx} & I_{zy} & I_{zz} \end{bmatrix}[/latex]

For example, think of an oddly shaped object attached to a drill bit off-center and wobbling about crazily as the drill spins. Fantastic. But the good news is that we get to dodge this bullet because we are always rotating about the center of mass of the go stone, our inertia tensor is much simpler:

[latex]I = \begin{bmatrix} I_{x} & 0 & 0 \ 0 & I_{y} & 0 \ 0 & 0 & I_{z} \end{bmatrix}[/latex]

All we need to do in our case is to determine the Ix, Iy and Iz values.

They represent how difficult it is to rotate the go stone about the x,y and z axes.

Interestingly, due to symmetry of the go stone, all axes on the xz plane are identical. So really, we only need to calculate Ix and Iy because Iz = Ix.

Numerical Integration

Let’s first calculate the inertia tensor via numerical integration.

To do this we just need to know is how difficult it is rotate a point about an axis.

Once we know this we can approximate the moment of inertia of a go stone by breaking it up into a discrete number of points and summing up the moments of inertia of all these points.

It turns out that the difficulty of rotating a point mass about an axis is proportional to the square of the distance of that point from the axis and the mass of the point. [latex]I = mr^2[/latex]. This is quite interesting because it indicates that the distribution of mass has a significant effect on how difficult it is to rotate an object about an axis.

One consequence of this is that a hollow pipe is actually more difficult to rotate than a solid pipe of the same mass. Of course, this is not something we deal with in real life often, because a solid pipe of the same material would be much heavier, and therefore harder to rotate due to increased mass, but if you could find a second material of lower density such that the solid pipe was exactly the same mass as the hollow pipe, you would be able to observe this effect. Obscure.

In our case we know the go stone is solid not hollow, and we can go one step further and assume that the go stone has completely uniform density throughout. This means if we know the mass of the go stone we can divide it by the volume of the go stone to find its density. Then we can divide space around the go stone into a grid, and using this density we can assign a mass to each point in the grid proportional to the density of the go stone.

Now integration is just a triple for loop summing up the moments of inertia for points that are inside the go stone. This gives us an approximation of the inertia tensor for the go stone that becomes more accurate the more points we use.

Interpreting The Inertia Tensor

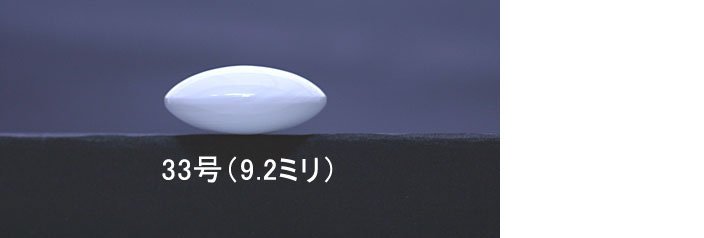

A size 33 japanese go stone has width 22mm and height 9.2mm:

Using our point-based approximation to calculate its inertia tensor gives the following result:

[latex]I = \begin{bmatrix} 0.177721 & 0 & 0 \ 0 & 0.304776 & 0 \ 0 & 0 & 0.177721 \end{bmatrix}[/latex]

As expected, Ix = Iz due to the symmetry of the go stone.

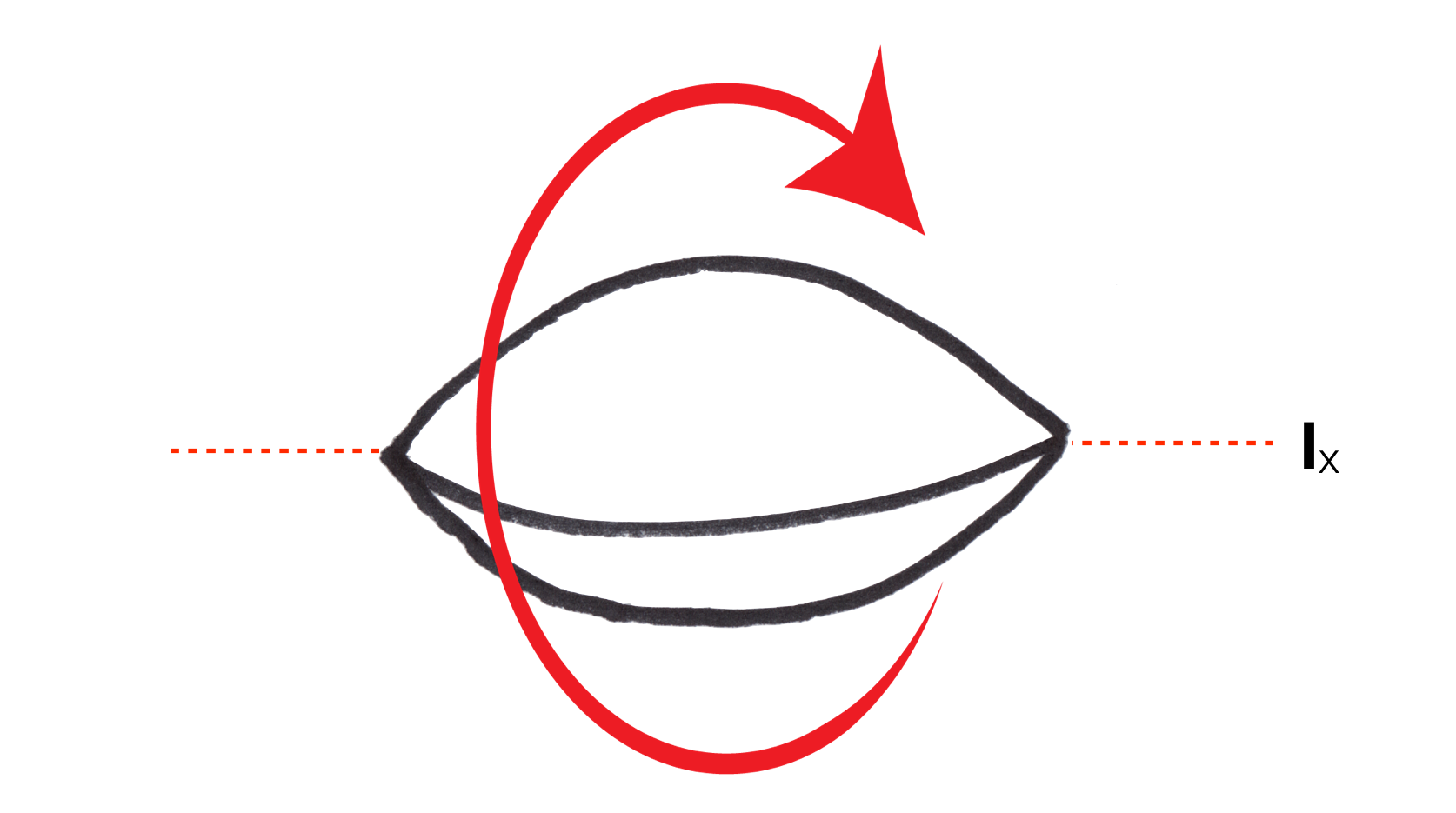

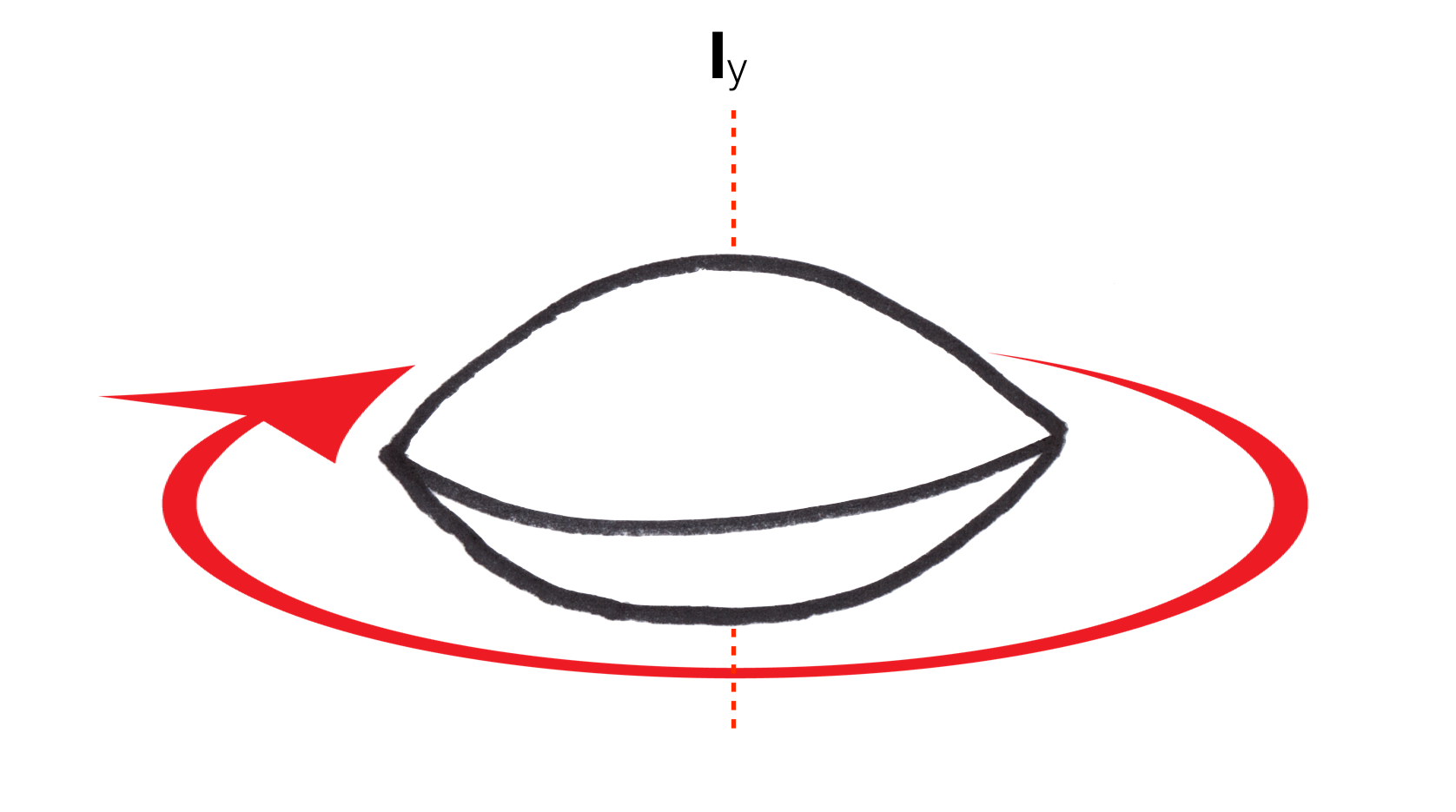

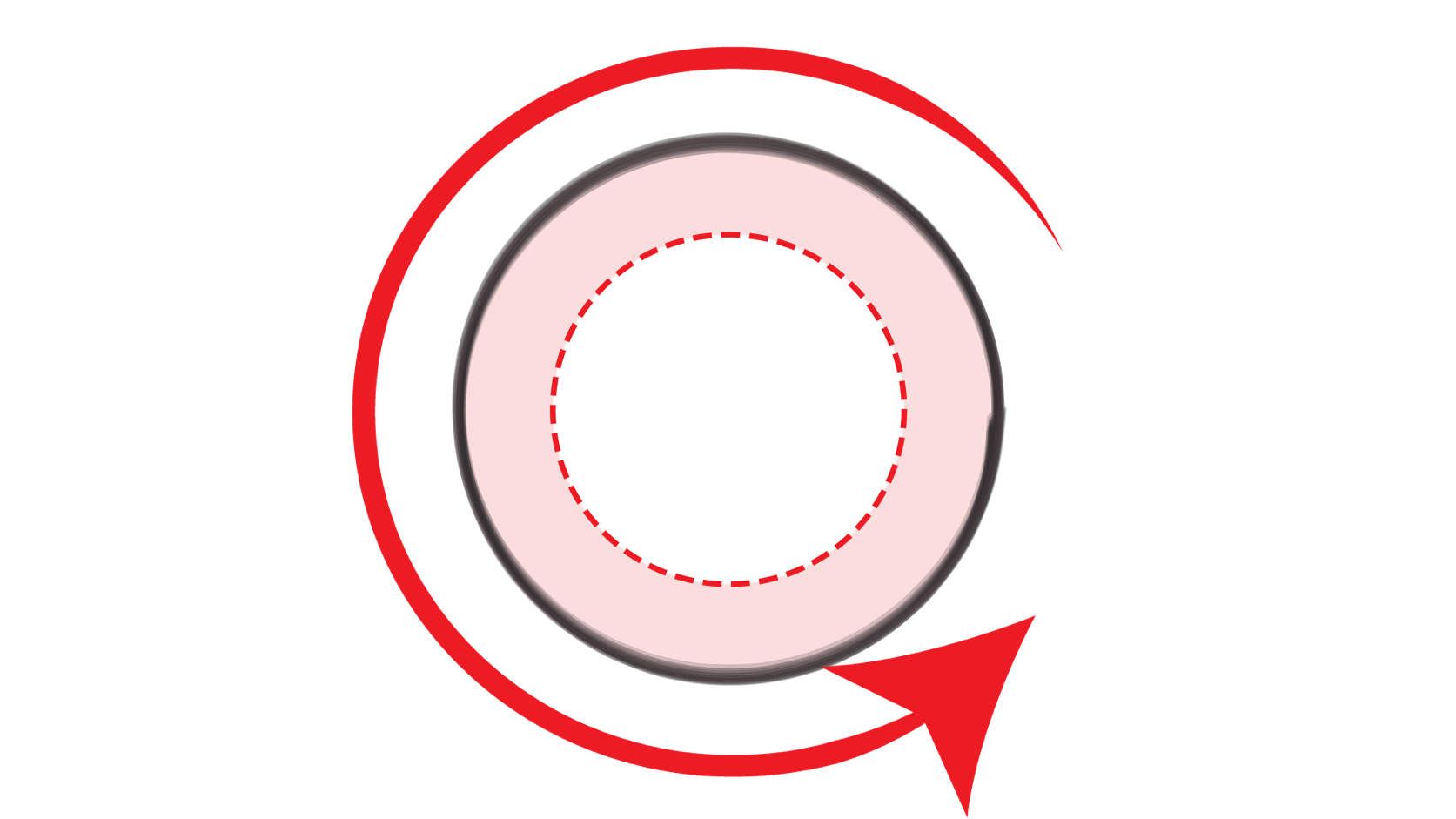

The inertia tensor indicates that its much harder to rotate the go stone about the y axis than axes on the xz plane.

Why is this?

You can see looking top-down at the go stone when rotating about the y axis a ring of mass around the edge of the stone is multiplied by a large r2 and is therefore difficult to rotate.

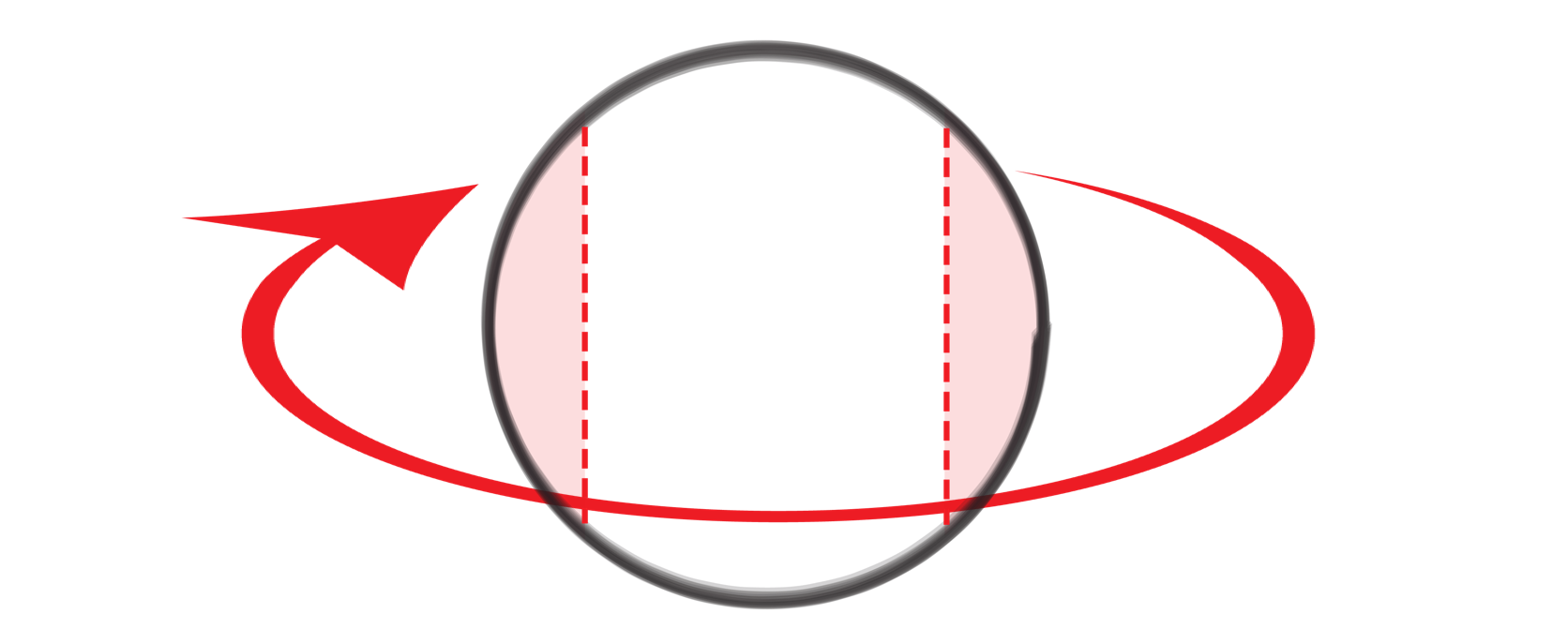

Contrast this with the rotation about the z axis, which has a much smaller portion of mass far away from the axis:

As you can see the distribution of mass around the axis tends to dominate the inertia tensor due to the r2 term. The same mass, twice the distance from the axis, is four times more difficult to rotate!

Closed Form Solution

Exact equations are known for the moments of inertia of many common objects.

With a bit of math we can calculate closed form solutions for the moments of inertia of a go stone.

To determine the exact equation for Iy we start with the moment of inertia for a solid disc:

[latex]I = 1/2mr^2[/latex]

Then we integrate again, effectively summing up the moments of inertia of an infinite number of thin discs making up the top half of the go stone.

This leads to the following integral:

[latex]\int_0^{h/2} (r^2-(y+r-h/2)^2)^2,dy[/latex]

With a little help from Wolfram Alpha we get the following result:

float CalculateIy( const Biconvex & biconvex )

{

const float h = height;

const float r = biconvex.GetSphereRadius();

const float h2 = h * h;

const float h3 = h2 * h;

const float h4 = h3 * h;

const float h5 = h4 * h;

const float r2 = r * r;

const float r3 = r2 * r;

const float r4 = r3 * r;

return pi * p *

( 1/480.0f * h3 *

( 3*h2 - 30*h*r + 80*r2 ) );

}

Plugging in the values for a size 33 stone, we get 0.303588 which is close to the approximate solution 0.304776.

Verifying exact solutions against numeric ones is a fantastic way to check your calculations.

Can you derive the equation for Ix?

NEXT ARTICLE: Collision Response and Coulomb Friction

Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com